Im pasting some of this onto this page - but all of it

plus the pictures - is on the pdf -

|

Im pasting some of this onto this page - but all of it plus the pictures - is on the pdf - |

Hermann Geissel

CRS Publications

-------------------------

Published by CRS Publications, 18 Weston, Newbridge, Co. Kildare

www.crsbooks.net

© Hermann Geissel 2006

ISBN 0-9547295-1-X

Design and layout by Bernard Kaye

Photography, except where otherwise credited, by Hermann Geissel

Map reproductions by kind permission of Ordnance Survey Ireland, Permit No. 8197.

Printed by Leinster Leader, Naas, Co. Kildare

This publication has received support from the Heritage

Council under the 2006 Publications Grant Scheme

-------------------

|

Contents The Eiscir Riada . . . . . . . . . . . ........................ . . . vi The Beginnings and the Television Documentary . .. . vii Colm O Lochlainn’s map of roadways in Ancient Ireland .. viii Preface . . . . . . ... . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .... . . ix Acknowledgements . . .. . . . . . . . ....... . . . . . . . . xi Chapter 1 – Áth Cliath Cualann . .. . . . .......... . . 1 Chapter 2 – Esker Riada . . . . . . . . . . ........... . . 7 Chapter 3 – St Mochua’s Road? ............... . . . . 9 Chapter 4 – Clondalkin . . . . . . . . . . . . .......... . 14 Chapter 5 – Donadea and Dunmurraghill . . ... . 19 Chapter 6 – Across the Bog . . .. . . . . ........ . . . 28 Chapter 7 – The Timahoe Toghers . .. . ... . . . . 31 Chapter 8 – Norman Castles .. . . . ............ . . . 37 Chapter 9 – The Long Ridge . .. . . . . ..... . . . . . 45 Chapter 10 – The Togher of Croghan ....... . . . 49 Chapter 11 – Rahugh . .. . . . . . . . . . ...... . . . . . 55 Chapter 12 – The Erry Way . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 61 Chapter 13 – Houses of Hospitality . .. . ......... . 67 Chapter 14 – The Big Bog . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 71 |

|

-------------------------------------

v

|

Annal M123 M123.0 The Age of Christ, 123. M123.1 The first year of Conn of the Hundred Battles as king over Ireland. M123.2 The night of Conn’s birth were discovered five principal roads leading to Teamhair, which were never observed till then. These are their names: Slighe Asail, Slighe Midhluachra, Slighe Cualann, Slighe Mor, Slighe Dala. Slighe Mor is that called Eiscir Riada, i.e. the division line of Ireland into two parts, between Conn and Eoghan Mor. From the Annals of the Four Masters |

...............................................

vi

The Eiscir Riada

‘… extended from High Street in Dublin to Áth Cliath Meadhraighe [Clarinbridge] in Galway. This esker, which is a continuous line of gravel hills, is described in our ancient MSS, as extending from Dublin to Clonard, thence to Clonmacnoise, and Clonburren, and thence to Meadhraighe, a peninsula extending into the Bay of Galway, a few miles South of the town. The writer has walked along this ridge, and found it to extend by the hills of Crumlin (Greenhills), and so along by Esker of Lucan, then south of Liffey, near Celbridge, and so across that river near Clane onwards to Donadea, until it strikes the high-road near Clonard, thus extending south of the conspicuous Hill of Croghan, until near Philipstown a line of road takes advantage of its elevation to run between bogs. It is next to be seen in a very conspicuous ridge two miles north of Tullamore, where Conn and Mogha fought the battle of Magh Lena, and thence it extends in a very well developed line through the Barony of Garrycastle until it strikes the Shannon at Clonmacnoise. It can be seen in a very distinct line at Clonburren, on the west side of the Shannon, and at the town of Ballinasloe, whence it extends in the direction of the Abbey of Kilconnell; thence it wends in the direction of Athenry, and soon to the promontory of Tinn Tamham (now Towan Point)* in Meadhraighe**, or the parish of Ballynacourty, a few miles south of the town of Galway’.1

From John O’Donovan,

|

‘Tracts relating to Ireland’ |

.....................................

vii

The Beginnings and the Television Documentary

After some informal earlier work on roads the author’s interest in the Slí Mhór was aroused during the investigation of a local road running east–west through North Kildare, known to local historians as St Mochua’s Road. Due to the saint’s link with Clondalkin, the study could not be limited strictly to County Kildare and was extended to include Dublin. When it was realised that the road in question represented a section of the Slí Mhór as outlined by Colm O Lochlainn in his 1940 paper, Roadways in Ancient Ireland, the search was extended to start at the ancient ford across the Liffey, the Áth Cliath Cualann, and to end at Monasteroris, O Lochlainn’s first landmark in County Offaly. The findings and conclusions were published in Oughterany, Journal of the Donadea Local History Group, vol. ii, no.1 (1999), under the title, ‘Via Magna in Ballagh, the Slí Mhór in Dublin and north Kildare’. The full article was also published on the author’s web site, but withoutthe endnote references.

The investigation was then extended across the rest of the island, and the topic was proposed to TG4 as a possible subject for a television documentary. The Director of Programmes received the proposal with enthusiasm and decided to commission a six-part series. Agtel/Independent Pictures were charged with the production. Key people involved in the production were

Conor Moloney Executive Producer

Ruth Meehan Producer/Director

Paul McCooey Presenter

Hermann Geissel Series Originator/Researcher

Seamus Cullen Researcher

Melanie Morris Researcher (Administration/Production)

The series was screened on TG4 in 2002 and repeated in 2003 and 2006.

..............................................

..........................................ix

This book is aimed at the general reader and gives a personal account of the investigation carried out by the author and Seamus Cullen in their attempt to map out the course of the legendary Slí Mhór. One of its aims is to convey the sense of wonder and excitement that drove the investigators during their quest, but it also presents the results of a serious search for the Great Highway.

Colm O Lochlainn, who in 1940 wrote Roadways in Ancient Ireland, accepted that the Slí Mhór largely coincided with the Esker Riada and extended from Dublin Bay in the east to Galway Bay in the west.2 For the present purpose, the route of the Slí Mhór was of greater interest than the Esker Riada, wherever the two appeared to diverge from each other. The Esker Riada as a geological feature was physically discontinuous but seems to have been a continuous landscape feature in the minds of the people.*

Apart from being the natural base of the Slí Mhór, it is said to have served as a political boundary during certain times of the First Millennium AD. No documentary account of its exact course is known, so it was considered futile to try and trace it in detail. On the other hand, the Slí Mhór as a major routeway would by its nature have to have been continuous. Despite numerous subsequent changes, its route would have left traces in the landscape; many recognisable on accurate modern maps and/or in the field. The route as described by Colm O Lochlainn was taken as a starting point and interpolations between O Lochlainn’s landmarks were made, based primarily on cartographic and topographical evidence. On several occasions the author disagrees with O Lochlainn’s conclusions. There was little or no work done by the present researchers to allow speculation regarding the accuracy or otherwise of O Lochlainn’s routes for the other four Slíte.

The preferred time frame is the early medieval period with Clonmacnoise and Durrow at their peak. The Slí Mhór is recognised as being primarily a road for students and pilgrims travelling between these monastic centres and the seaports of Dublin/Howth and Clarinbridge/Kilcolgan (with extensions beyond these termini to the Aran Islands, but also to the western Mediterranean). Traders would have used the road frequently, as well as people going to the fairs. Since most of the major military conflicts of the time were between the Ui Néill of Tara on the one hand and Leinster or Munster on the other, the Slí Mhór with its almost perfect east-west orientation would not have served well as a military road, minor localised troop movements connected with the raids on Clonmacnoise etc. notwithstanding. It is recognised that with the decline of Clonmacnoise and the growing importance of Athlone, aided by the construction of a bridge there in 1210, the dominant east–west route took a more northerly course and gradually evolved into the present N4/N6 road system from Dublin to Galway.

Since many of the road users would have travelled on foot, it was imperative that they use the shortest feasible itinerary. Therefore looking for short and reasonably straight routes became a guiding principle of the research.

Steep gradients would not have been serious obstacles prior to the beginning of stagecoach travel in the seventeenth century.

The claim that the five Slíte were the great prehistoric highways converging on Tara is briefly dealt with in Appendix VIII, but is broadly dismissed in favour of the accepted Esker Riada/Slí Mhór congruity

x

between the Slí Mhór as outlined and roads to Tara are nonetheless suggested in Appendix VII.

The map details reproduced are mostly taken from the maps of the OSI 1:50 000 DISCOVERY SERIES. Where the superimposed markings obscure certain map features, the reader may wish to consult unmarked maps independently. Older and/or larger scale maps often provide additional information; so would soil maps, occasionally. The research methods employed are described in Appendix I but will also become apparent in the narrative and map captions.

Some reference to historical events, traditions and legends is made and some geological, ecological and socio-historical background is given to provide perspective. These matters are considered secondary to the geography of the roads and are therefore not discussed or evaluated, as critically as the main issue.

The author has presented the more important research results as entries on the map details reproduced in the book, with explanatory captions.

The rest is his story.

...............................................

This publication has been made possible with financial assistance from the following:

The Heritage Council

Offaly Historical and Archaeological Society

Offaly County Council

National Roads Authority

Galway County Council

Kildare County Council

South Dublin Libraries

Anglo Irish Bank Corporation

xi

Researching the Slí Mhór and writing this book has been a very pleasant experience for me, which is to a large extent due to the help and assistance I received from a number of individuals and organisations. The help and companionship of Seamus Cullen not only made the field and cartographic work a very pleasant experience, but his keen eye for topographical features, however subtle, and his encyclopaedic knowledge of local history complemented my own work in a significant way. When I was away, working as a tour guide, prior to the television production, he carried out some of the documentary research and liased with television producers and prospective interviewees. We received great assistance from the Offaly Historical and Archaeological Society and were given access to their considerable resources. My thanks go to the County Libraries of Kildare, South Dublin, Westmeath, Offaly and Galway.

The Ordnance Survey of Ireland assisted us with maps and aerial photographs and has generously given permission to reproduce the map details included in the book. I remember with pleasure and gratitude the numerous stimulating conversations Seamus and I had, individually or jointly, with Michael Byrne (OHAS), Mario Corrigan (Kildare Co. Library), Eoghan Corry, Ted Creaven, Tony Doohan, Paul Duffy, Dr John Feehan (UCD), Richard Flynn (OSI), Fred Geoghegan, Councillor Constance Hannafy, Kieran Hoare (NUI Galway), Dr Kieran Jordan, Martin Kelly, Tom Longworth, Tony McEvoy, Steve McNeill (OHAS), Malachy McVeigh (OSI), Gerry Mallon (OSI), Maria Mannion (Galway Co. Council), Peadar O’Dowd, Amanda Pedloe (Offaly Co. Council), Niall Sweeney (Offaly Co. Council), Kiaran Swords (South Dublin Libraries), Tom Varley, Dr William Warren (GSI) and the late Noel Whelehan (Edenderry Library). A number of persons read various drafts of the manuscript, made valuable and thought-provoking suggestions and gave me great encouragement. My special thanks to them for their help, and my apologies if the end product does not do their suggestions justice. They include John Bradley, Dr Niall Brady, Thaddeus Breen, Mairead Evans, Conor McDermott, Eleanor McNicholas, Adrian Mullowney, Jim Parker, Professor Etienne Rynne, Dr Matthew Stout and my daughters-in-law, Carmel and Eileen.

Map reproductions by kind permission of Ordnance Survey Ireland, Permit No. 8197. Aerial photos of Clonmacnoise courtesy of the Photographic Unit, Dept. of the Environment, Heritage and Local Government.

Hermann Geissel July 2006

Acknowledgements

..............................................

............................................

1

I had been to Howth on some errand and was driving back towards Dublin. Having come up the coast road on the way out I decided to take the Howth Road on the way back. Since I was at the time taking an interest in historic roadways in the Dublin/Kildare area,

I had made it a habit to keep an eye out for roads running on ridges or on terrain elevated above the surrounding countryside, wherever I went.

The road I was travelling on appeared to fall into the pattern I had mcome to expect: riding the brow of a low ridge with the land falling off to both sides. It’s one of those again, I realised. Amazing. My senses were awakened as I followed it, and yes – it went all the way.

No, it didn’t: when I had reached the Royal Canal bridge on Summerhill Parade, the road left the high ground. In order to stay on firm, dry land, it should have continued roughly in line with the North Circular Road, heading for Phoenix Park. So why didn’t it?

Gradually it dawned on me: the road was heading for the ford – the ancient ford across the River Liffey. I proceeded down into Parnell Street, to where it intersected with Capel Street. Surely it had to continue? There was a little lane ahead that just about allowed my car to pass through: Britain Street, continuing as Cuckoo Lane. What a charming name! Yet things became more confusing after that. The lanes grew narrower, and they didn’t line up.

Nonetheless, I came fairly close to the area where the old ford was said to have been.

Map 1: The ford (white).

Four ancient roads approach the river crossing from the north: Stoneybatter, Upper Church Street, Bolton Street and Parnell Street (blue, from left). A townscape (outlined green) bordered by Blackhall Place, North King Street, Capel Street and the Quays (clockwise, from left) masks their continuation. Inside this area an old road survives as Bow Street (orange), changing to Lincoln Lane upon reaching the former floodplain, before reaching Arran Quay. Bow Street appears to be the original continuation of Upper Church Street — Lower Church Street being a later diversion to provide access to the bridge.

Lincoln Lane (red outline) would have been within the tidal zone of the river before the latter was contained between the quay walls.

On the south side St Augustine Street (yellow) would have pointed straight at the ford (Usher’s Island) before it was curved to meet Usher’s Quay at right angles.

The Slí Mhór started on High Street, heading for Marrowbone Lane.

|

Chapter 1 Áth Cliath Cualann (Map 1) OSI DISCOVERY SERIES, Sheet 50 © Ordnance Survey Ireland/Government of Ireland |

.............................................................

2

I went home and started poring over a city map. Yes, here was the answer: the street pattern had been changed. I began to see the difference between a street and a road (a linguistic problem I have carried around with me for more than half my life, since in my native German there is only the one word, Straße). Well, there was clearly a need here to distinguish between a road and a street. I decided to let the word road denote an evolved country road that existed before there was a town built around it, or, in the case of Dublin, before the town began to extend over it, and a street to signify anything from an alley to an avenue that was part of a planned town or cityscape.

Looking at my map I could see that there was a system of streets in a roughly rectangular area bordered by Blackhall Place, King Street, North King Street, Capel Street and Arran Quay. I blanked out that area in order to see better what was outside it, and there were more roads! Apart from Parnell Street, there were Bolton Street, Upper Church Street, Stoneybatter. They all looked like old, evolved country roads. And they were converging. Of course they were: they were all leading to the ford. At that stage I felt the challenge to find the site of the ancient river crossing. I had no idea what it would lead to.

The old Hurdle Ford is remembered in Dublin’s Irish name, Áth Cliath. Most of the literature I was familiar with said that the exact location of the ford was not known.* One book I had read says it was near the mouth of the Poddle,3 and another says it was just upstream of Church Street Bridge (alias Father Matthew Bridge).4 I dismissed the former hypothesis out of hand when I took another look at the old road pattern. It had to be near Father Matthew Bridge, which was built on the site of the oldest Liffey bridge in Dublin.5 But the ford could not have been at the same location as that bridge, as the great Dr Joyce had maintained one hundred and thirty years ago and as is still widely believed.6 Certainly, as Joyce points out, an imagined extension of Stoneybatter lines up very well with the northern end of the bridge at Arran Quay. But at the time of the ford the river would have been much wider than it is today, especially to the north where there is no steeply rising high ground to contain it. Besides, bridges were not built over fords; fords would have been in use while the building works went on, so the bridges had to be built a short distance away. Allowing for the greater width of the river, the ford had to be upstream of the bridge. Ancient road systems are generally older than the bridges that carry them across rivers. Bridges were built to facilitate existing roads, not the other way around. Only when the bridge was built would a short length of the road be diverted away from the ford to meet the bridge. So when looking for a ford, it is always good to look near a bridge, or, where there are several to choose from, as in Dublin, then to look near the oldest bridge.

All this reasoning merely confirmed what was already known, but would I be able to improve on the accuracy of the ford’s location in any way? I looked at my copy of the street map with the area bordered by Blackhall Place, North King Street, Capel Street and the Quays tippexed out. With a pencil I drew extensions of my four roads to see where they would have met. Oh, they met all right – wherever I wanted them to meet!

It was too simple. One cannot assume that the roads would have extended in straight geometrical lines. Just drawing straight lines was too easy a way out of it. But it was what Edward de Bono, the intellectual father of ‘Lateral Thinking’, would have called the ‘Intermediate ‘Intermediate Impossible’. A stepping stone in the search for a new solution to an old problem.

* The narrative here recounts the research done some time back, before the Irish Historic Towns Atlas (No.11) was published. See Appendix II for a discussion of recent alternative hypotheses.

........................................................................

3

Where would I find another clue to limit my all-too-wide choice? I went back to Dublin to walk the area, when I saw it: Bow Street, which I had deleted from my map as one of the streets, was in fact a road! At this stage I was beginning to develop a feel for it, an intuitive hunch about a road’s character, based on cryptic clues as to its age, too obscure to explain rationally. Somehow Bow Street looked different on the ground than on any of the maps. I was blessing my luck that the street map I had been using, though thirty years old and quite out of date, gave more of a clue than any of the more modern ones I consulted later in the hope of getting a better picture. Even looking at a former Soviet Spy Satellite image on the Internet didn’t improve on what the first map had indicated.

Yet it did look different on the ground. There is a fair rise (or fall, if you are coming from the north) in Bow Street. It comes down from raised ground and descends until it reaches the totally level, low-lying land which I later decided to interpret as having been a part of the river’s tidal flood plain. It was the broad riverbed, as it would have appeared before the river was constrained in its present course by the quay walls. At this point Bow Street crosses Hammond Lane/North Phoenix Street and continues as a narrow little alley known as Lincoln Lane. Lincoln Lane had to be the ford, or a causeway leading down to the ford! And Bow Street (Bow Road?) was leading directly to it!

New questions arose. Was the entrance to the ford too far away from the present riverbank? Not really. It is known Father Matthew Bridge, viewed from the west. Though not the original bridge at this location, it marks the site of the oldest bridge over the Liffey in Dublin. The dome of the Four Courts is visible in the background.

The picture was taken from the probable exit of the hurdle ford at Usher’s Quay. Lincoln lane (above right) must have been a part of the ancient Áth Cliath ford, or alternatively marks the site of a former causeway leading down to it.

The crossing with Hammond Lane at the end of the double yellow line is the beginning of Bow Street, an old road (i.e. not a part of a planned streetscape) coming down from high ground and leading directly to the ford.

..........................................

that the Liffey was up to 300 metres wide in places, and here the distance was less.

Would the other four roads have met at the bottom of Bow Street?

They did. If I wanted them to. I took another look at the streets previously erased from my map. There was Lower Church Street, diverting from the direction of its Upper sister to meet the bridge – away from the ford. But why didn’t it go on in a straight line from the bend to the bridge? Again the answer was right there: the street was diverted to avoid the church: St Michan’s. St Michan’s Church had been founded by the Norse in 1095; it had been built several decades before the Normans arrived.7 Predating the bridge, it necessitated a slight diversion of the access road.

Still I was looking for more evidence to support my hypothesis, and I found it on the south side of the river. Upper Bridge Street comes down from the Cornmarket, taking a sharp turn at the traffic lights where its name changes to Lower Bridge Street. Is it another instance, as in the case of Church Street, where the road was redirected away from the ford, to meet the bridge? Perhaps. Close by is St Augustine Street. Going down towards Usher’s Quay, it takes a slight right turn before getting there. If continuing straight instead of turning it would arrive opposite Lincoln Lane. One of them had to be the original ascent from the ford to the high ground at Cornmarket. More likely St Augustine’s, but either would have fitted the bill.

Perhaps significantly, there is a pub on Lower Bridge Street, claiming to be the oldest pub in Ireland, founded in 1198. I always liked that date. I reasoned that if the Normans arrived in Ireland in 1169 entered Dublin a year later, perhaps they got busy soon after and started building a bridge across the Liffey. Then some sharp businessman saw the opportunity to open an inn on what would promise to be a lively route. However, King John’s Bridge, the first of a succession of stone bridges at this location, was not built until 1214.8 Maybe there was a wooden bridge, not recorded, a few years earlier. Who knows?

Going back to the alternative hypothesis that the original ford, the Áth Cliath, was further down-river, one might argue that there were two Celtic settlements above the banks of the Liffey, Áth Cliath, by the Hurdle Ford, and Dubh Linn, by the ‘Black Pool’. Did each settlement have its own ford across the River? It is unlikely, seeing that the ford was not a natural shoal of rock or permanent gravel across the riverbed. It had to be built and needed to be maintained by the people using it and was then still a risky crossing. After all, it is said that a whole army once drowned here, trying to cross the Liffey at high tide. But even if there had been a second one – the ancient settlement above the ford near Christ Church was, for all to know, called Áth Cliath.

4

Before the Ford was built

If a hurdle ford is manmade, how did people get across before it was built? Paul Duffy, an engineer and hydrologist, tells me that by the interaction of the river currents with the changing tides, sandbars were deposited across the riverbed on which people could cross. These low ridges or shoals would come and go and change location, so they were rather unreliable. The building of access roads in fixed locations required a permanent ford, so a hurdle ford was built as a more permanent crossing point.

It is of interest to note that the name, Béal Feirste (Belfast), means the mouth of (entrance to) the sandbank.

Broadly speaking, few fords were naturally well enough suited for their purpose that they did not require some improvement.

Flagstones, gravel or wickerwork were normally used to improve the passage through the river.

....................................................................

5

It is said that the ford was built in AD 31 on the instructions of the Ulster poet, Aithirne, called ‘The Importunate’.9 Aithirne stood in the service of his king, Connor mac Nessa, and had taken it upon himself to collect the bóruma (bóraimhe) from the other provincial kings. This tribute consisted not only of cattle and other livestock, but also of slaves and hostages.

Aithirne reputedly started his tour of the island from the royal residence of Eaman Macha (Navan Fort near Armagh) and, going in an anti-clockwise direction, travelled through Connacht, Munster and finally Leinster, then across the River Liffey at the (Dublin) ford before reentering home territory.

The Dublin ford was called Áth Cliath, the ‘Ford of the Hurdles’. These hurdles were wooden panels, made of interwoven branches of hazel or willow, similar to those a shepherd would have used to construct a fold for his flock.

The panels were placed on the bed of the river to provide a reasonably firm floor for people and animals to walk on and for light wheeled vehicles like chariots to drive over.

The river in the area would have been more than 200 metres in width, though at low tide it would be confined to a deeper and rather narrow channel. We know about other places where rivers were widened to make them shallower and fordable, and this was probably done here by in-filling the channel, thus forcing the water of the Liffey to spread out over much of the available width otherwise flooded only at high tide. Then the hurdles would have been put in place, pegged down and weighed down with heavy stones.

At low tide this would leave a very shallow flow of water, easy to wade, ride or drive through, but problems have been known to arise nonetheless. It is reported in the Annals of Ulster that in AD 770 a Ciannachta army from

The Brazen Head pub claims to have been established in 1198. If that date is correct then there should have at that time been a bridge on the site of the present Father Matthew Bridge (a.k.a. Church Street Bridge), even though the first stone bridge was only built here in 1214.

The picture shows a section of an excavated hurdle togher. A hurdle ford would have been constructed from similar units. (From Raftery, 1996).10

............................................................

6

Brega, a Celtic kingdom whose extent roughly covered today’s County Meath but reached down as far as northern Dublin (Fingal), made an incursion into Leinster.

They defeated in battle their enemies, the Uí Téig, who lived in the present County Wicklow, between the Great Sugar Loaf and Rathdrum.12 But subsequently many of the Ciannachta army drowned on the way home when trying to cross the Liffey at the Áth Cliath. The tide must have caught up with them. Or a flash flood.*

Fascinating as the Áth Cliath and its converging roads are in their own right, there was now more work to be done. I was at the time doing some research on the Slí Mhór in Dublin and north Kildare.** In the present investigation this earlier work was to be continued and an attempt made to track this legendary road, one of the five ancient ‘highways’, or Slíte, all the way across the Irish Midlands and to the west coast. In the beginning I was not sure whether I was looking for the Slí Mhór or the Esker Riada, accepting initially that the two were one and the same, as it says in the Annals of the Four Masters and elsewhere.*** In the course of my research I came to the conclusion that this was not always the case.

Aithirne ‘The Importunate’

I first came across his name some years ago when doing some research on Clane, County Kildare. As the story goes, Aithirne had rather stretched the patience of Meas Geadhra, King of Leinster, when he made off with his booty of flocks and fat herds, a far-extending throng, bondsmen and handmaids, beautiful and young as Sir Samuel Ferguson superbly put it in his poem about the duel by the ford at Clane. While Aithirne was a guest in the Leinster king’s territory, Meas Geaghra had to treat him according to the strict rules of hospitality and could not deny a man of such high status any request, however unreasonable.

But now that the poet had left the realm he could no longer expect to enjoy such privilege, and the king followed him across the river, laying siege to the Hill of Howth. Aithirne called for help, and the Northern Champion, Conall Cearnach, came to his rescue and drove Meas Geadhra back, finally killing him in a duel by the Liffey ford at Clane, County Kildare.

Dr Joyce reports an even more gruesome story: Eochy [Eochaid] mac Luchta was at the time [when Aithirne made his round] King of south Connacht and Thomond, and had but one eye. The malicious poet, when leaving his kingdom, asked him for his eye, which the king at once plucked out and gave him; and then desiring his attendant to lead him down to the lake, on the shore of which he had his residence, he stooped down to wash the blood from his face.

The attendant remarked to him that the lake was red with his blood; and the king thereupon said: Then Loch-Dergdherg [pronounced Dergerc] shall be its name forever; and so the name remains…. The present Lough Derg is merely a contraction of the original.11

|

* Can we uncharitably assume that they may have been celebrating their victory? *** See p.v |

...................................................................

7

The Esker Riada is a remarkable landscape feature, seen by the people of ancient Ireland to extend right across the centre of this island, dividing it into two halves of amazingly similar area. It is a long chain of linear gravel hills, relics of the last Ice Age, which people joined up mentally into a continuous ridge of high ground, serving both as a boundary and as a routeway.

These eskers are some of the more fascinating features of the Irish landscape, the word derived from the Irish eiscir.

They are elongated gravel ridges, often extending over many kilometres, sometimes narrow and steep-sided, sometimes wide and gently sloped, often undulating or beaded and frequently branched or fanned. They were formed at the end of the last ice age and are mostly found along the discharge outlets between neighbouring domes of ice. Most eskers in County Mayo and in Kildare/Carlow run in a north-west–south-east direction, but in Offaly and sporadically elsewhere they are generally aligned east–west.

Because they formed in the turbulence of flowing meltwater, the finer soil particles like silt and clay were washed out and escaped with the water. They were deposited elsewhere, when the flow had come to a standstill and the clay had a chance to settle, much of it in temporary post-glacial lakes. Larger aggregates were tumbled about, rubbing the edges off one another, resulting in stones that were well rounded: essentially round boulders, cobbles, pebbles, gravel and sand. Eventually these were deposited in the riverbed, often in distinct layers as the speed of the flowing water allowed it.

It is not too difficult to recognise an esker, if we use the term loosely. Generally speaking, the land falls off to both sides from its long axis. Eskers often undulate, sometimes showing alternating humps (‘beads’) and depressions, reflecting the seasons during the melting process: more ice melted during the summer, resulting in the deposition of more material. Surface stones in tilled fields or recent excavations are always rounded and often represent different rock types, originating in different regions, reshuffled by the glacial melt-water.

Human activity along eskers has resulted in the construction of roads atop the ridges, the opening of gravel pits along their sides (sometimes serving an ultimate purpose as landfill sites), or the building of golf courses. Next to the famous links in the coastal dunes of Lahinch, Portmarnock or Ballybunion, golf courses on esker ridges have been most popular with their excellent natural drainage and uneven surface features, very desirable for the golfer’s purpose.

Nor is there a shortage of esker cemeteries, for obvious reasons.

For the amateur enthusiast who likes to carry out a geological investigation while driving a car at 120 km/h, an excellent example of an esker can be studied when travelling on the Newbridge bypass. Coming from Dublin or Naas, shortly after the M9 branches off the M7, the second bridge connects two parts of a major ridge that carries the Old Connell road. The ridge is deeply cut out under the bridge, with no bedrock visible on the smoothly sloping banks. Before and after passing the ridge the motorway is generously raised above the surrounding countryside, the gravelly material removed from the esker providing excellent and readily available fill for the embankment. If the driver is interested in more post-glacial geology, he/she might notice a kettle hole on the high ground to the left of the motorway, shortly the ridge. This came about when a

Chapter 2

Esker Riada*

* See Appendix IX.

....................................................................

8

Map 2: Detail of Colm O Lochlainn’s map, showing the Slí Mhór.

This route was taken as the starting point for the current project. massive lump of dead ice had gravel and rubble dumped upon it by the receding ice sheet. When the ice finally melted, the ground above it collapsed, and an almost perfectly round hole was formed.

Motorists travelling from Dublin to Galway on the N6 have to cross a very prominent esker shortly after Tyrrellspass, apart from travelling on a less spectacular one much of the time – perhaps without realising it. In the Dublin area, the Greenhills Road between Walkinstown and Tallaght and the Esker Road near Lucan are striking examples. Natives of County Offaly and some of the northwestern counties have of course known eskers ever since they started travelling the countryside in perambulators.

Alas, some eskers have all but disappeared due to the harvesting of sand and gravel.

While generations of Irish people have thought of the Esker Riada as a continuous ridge across the width of the country, no such continuity exists in reality. Eskers may end suddenly and can be interspersed with extensive areas of soft lowland, bog or expanses of scantily covered limestone rock.

Elsewhere two or more eskers may run parallel or intersect obliquely, making the search for the real Esker Riada no less confusing. I was unaware of any accurate or detailed account of the course taken by this legendary boundary between the northern and southern halves of this island. Nor are there any records of it on reliable maps or convincing clues in the landscape, clues that would allow the researcher to join the dots where lengthy stretches of the esker simply don’t exist. Therefore I considered it futile to attempt to delineate the topographical feature of the Esker Riada as a continuous line, and decided to concentrate on the search for the road. Once the road was identified, I reasoned, it would perhaps be possible to draw some valid conclusions about the course of the more elusive Esker as well.

.....................................................................................

9

The Slí Mhór was one of five Slíte or main highways which, according to the Annals of the Four Masters, all led to Tara.

Colm O Lochlainn in his 1940 essay, Roadways in Ancient Ireland, has mapped these roads, along with many minor ones, and his map shows a clear convergence of four of these highways on Dublin.13 He suggests that perhaps a powerful king like the legendary Cormac Mac Airt built access roads from Tara to pre-existing routes that might have been in use for centuries before his time. I will briefly deal with the Tara connection in the Appendix VIII, but for the present project I have chosen to explore in some detail the route from Dublin to Clarinbridge, following O Lochlainn’s outline.* While O Lochlainn’s work is based largely on documentary sources, our research builds on it and makes ample use of maps, both old and modern, and takes a close look at the topography along the route.

Starting out from Dublin, there are different courses that the Via Magna – as the Great Road is referred to in Medieval Latin – may have taken. In the twelfth-century Book of Leinster it is stated that the Slí Mhór passed through Clonard,14 and a good argument can be made for that alternative, while other sources favour a route passing through north Kildare and Offaly, crossing the Shannon at Clonmacnoise. In the end it may come down to little more than local pride when a person decides to go for one version or the other, but O Lochlainn definitely favoured the southern route. Personally I had absolutely no problem with the latter version, since I was at the time researching an article for a north Kildare local history journal, unashamed of my parochial interest in the history and geography of that particular region.15 Still, I hope to be able to make a more convincing case for the southern route as we go along – my personal bias notwithstanding.

As O Lochlainn tells us in his 1940 paper, the Esker Riada/Slí Mhór started in Dublin and went from there to Lucan and Celbridge. Trying to trace that roadway to Lucan, it is not hard to see high ground following Thomas Street, Bow Lane, Kilmainham Lane into Kilmainham, Inchicore and Ballyfermot.

|

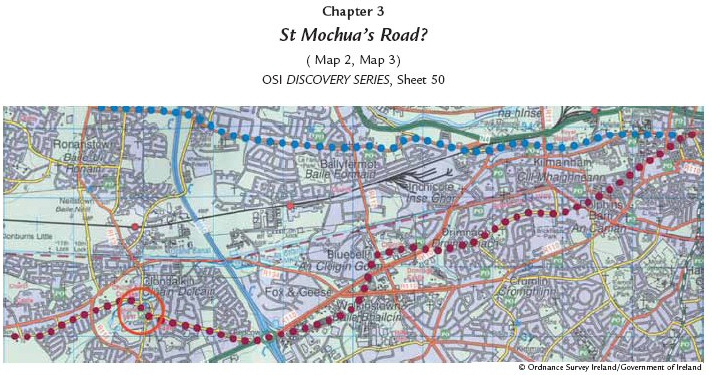

Chapter 3 St Mochua’s Road? OSI DISCOVERY SERIES, Sheet 50 Map 3: Dublin (Cornmarket) to Clondalkin. Traditionally, the course of the Slí Mhór is said to have started in Dublin’s High Street, near Christchurch Cathedral. Extant street/road patterns suggest that it continued via Cornmarket, Marrowbone Lane (the curved, northern part), Mourne Road, Drimnagh, Old Naas Road, Robin Hood Road, Red Cow Roundabout, Monastery Road into Clondalkin and out by the old Nangor Road. The red circle marks Clondalkin’s old monastic centre. © Ordnance Survey Ireland/Government of Ireland |

......................................

10

From the Ballyfermot roundabout it continues along the present road past Cherry Orchard Hospital, then Coldcut Road and further on to Lucan. The Lucan area is replete with placenames old and new containing the word esker as an element (though the most spectacular Esker Road from Lucan to Ronanstown is not in line). After Lucan it is possible to see a low ridge of high ground (though not quite continuous) extending to Celbridge, south of the modern road.

O Lochlainn says the Slí Mhór went that way.

Anglo-Norman Motte at Clonard, County Meath. The twelfth centuryBook of Leinster states that the Slí Mhór passed through Clonard.

While there can be little doubt about the importance of Clonard as an Early Christian teaching centre, the position taken here contends that the road via Clonard and Athlone became the important east— west axis only in Anglo-Norman times. An early medieval route linking Clonmacnoise with Clonard has been identified (Appendix VII). It may even have been part of a road to Tara.

|

Table 1: The five Slíte (after O Lochlainn). O Lochlainn suggests that they represent old established routeways from which link roads were built to bring them together at Tara. |

|

|

Slí Mhidhluchra |

Derry – Armagh – Newry – Dundalk – Drogheda – Dublin |

|

Slí Assail Rathcroghan |

– Longford – Slane – Drogheda |

|

Slí Mhór Clarinbridge |

– Ballinasloe – Clonmacnoise – Timahoe – Celbridge – Dublin |

|

Slí Dhála Tarbert |

– Limerick – Roscrea – Abbeyleix – Kildare – Dublin |

|

Slí Chualann Waterford |

– Ross – Leighlinbridge – Dunlavin – Tallaght – Dublin |

------------------------

23

11

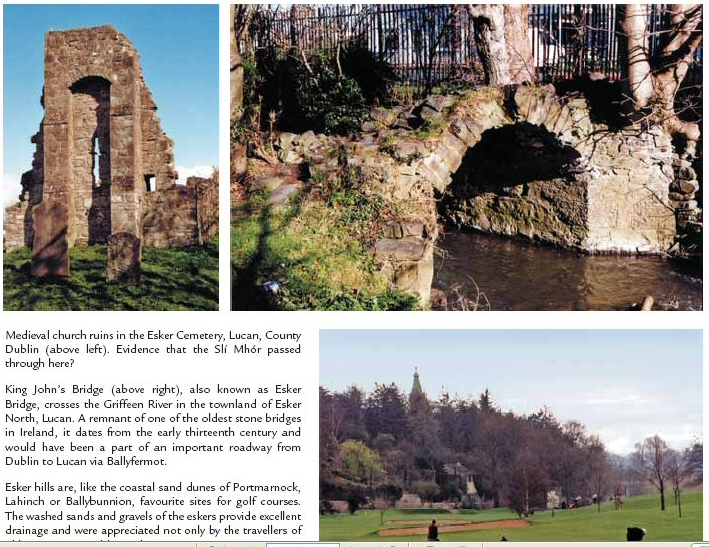

Medieval church ruins in the Esker Cemetery, Lucan, County Dublin (above left). Evidence that the Slí Mhór passed through here?

King John’s Bridge (above right), also known as Esker Bridge, crosses the Griffeen River in the townland of Esker North, Lucan. A remnant of one of the oldest stone bridges in Ireland, it dates from the early thirteenth century and would have been a part of an important roadway from Dublin to Lucan via Ballyfermot.

Esker hills are, like the coastal sand dunes of Portmarnock, Lahinch or Ballybunnion, favourite sites for golf courses.

The washed sands and gravels of the eskers provide excellent drainage and were appreciated not only by the travellers of old. Lucan, Co. Dublin (right).

------------------------------------------

12

Furthermore, the ecclesiastical site of Balraheen was dedicated to him, and Timahoe (Tigh Mochua) is believed to have been named after the same saint. It is easy enough to drive from Clondalkin to Timahoe, through Celbridge and past Balraheen, hence local researchers in North Kildare have been tempted to call this road St Mochua’s Road.16 |

|

It was therefore quite conceivable that a similar chain of events had taken place in the case of St Mochua; that he went to live his solitary life at Clondalkin when soon he found himself surrounded by a group of followers, then went west to Celbridge, where the process repeated itself, then to Taghadoe, Balraheen and so forth until he finally came to rest in Timahoe.

|

Unfortunately, there are certain problems with this line of argument. St Mochua – whose name originally was Cronan Mac Lugdach, later changed to Mo-chua* – is said to have been Abbot and probably also Bishop of Clondalkin, which does not harmonise well with the image of a hermit on the run.18 Celbridge has definite links with the saint.19 An old graveyard still contains St Mochua’s Church, and there is also an old inscribed stone slab in existence that formerly marked St Mochua’s holy well. |

|

||||

Taghadoe (Tech Tua), however, is named for another saint, Ultan Tua (the Taciturn Ulsterman). The Taghadoe settlement had strong links with Clane and at one time shared its abbot with the Clane monastery.20 The founder of Balraheen is not known, but its association with St

----------------------------------------------------------

13

Mochua is documented.22 Before we proceed to Timahoe, we pass two more ancient monastic sites en route, neither of them directly connected with Mochua. The first is Clonshanbo, associated both with St Garbhan, a brother* of St Mochua, and with St German. The other site is Dunmurraghill, linked to St Patrick, who is said to have founded there a domus martyrum or martyr house (a graveyard); also in the area is a holy well dedicated to StPeter.

Neither does St Mochua appear to be the founder of Timahoe nor is there any record or tradition that he died there. The name, Tigh Mochua, is the only link.24

We may therefore conclude that while St Mochua has some but by no means exclusive associations with that road and probably would have used it in his travels, yet we cannot go so far as to hold him responsible or give him credit for its origins. Nor is it likely that the road was built during his lifetime; it must have been in use before his day

** At the risk of overstating the case, Clondalkin was a most unlikely place for a hermit since it was located on another ancient highway, and as we shall see, Timahoe was far from being a dead-end peninsula jutting haplessly into impenetrable bog.

|

Table 2: Five categories of road according to the Law Texts.21 |

|

|

Slí (here spelled slige) |

a highway; the widest of the roads, must allow two chariots, each drawn by two horses, to pass. Originally the word slige may have been applied to paths hewn through forests. As a verb it means hacking or clearing and would be cognate with German schlagen, which in a forestry context means to fell. |

|

Rout (an earlier spelling of ród) |

a (secondary) road; sometimes used as a generic term for any type of road |

|

Lámraite |

a byroad |

|

Tógraite |

a curved road |

|

Bóthar |

a cow track; must fit two cows, one sideways and one lengthways |

|

* It is known that St Mochua had a brother of that name, and given the proximity of Clonshanbo to Celbridge and Clondalkin, it is likely that he was the manin question. ** I don’t believe that St Mochua of Clondalkin, if indeed he was identical with Cronan Mac Lugdach, was a contemporary of St Kevin’s, either. A string ofsuccessors mentioned in the Lives of the Irish Saints all have death dates given in the eighth century, so St Mochua probably flourished in the late seventhor early eighth century. There was also another St Mochua (alias Cronan) of Balla who flourished c. AD 600. The occasional confusion of the Clondalkinsaint with St Mochua of Timahoe in County Laois cannot be ruled out either. |