Tara and Lismullin

3. ARCHAEOLOGICAL ASSESSMENT ( OFFICIAL )

3.1 Archaeological and Historical Background

A general introduction to the archaeological background is provided below. It is a synopsis of the

information contained in EIS Vol. 4A carried out by Dr Annaba Kilfeather on behalf of Margaret

Gowen and Company Ltd. (with additions).

General

Human occupation in Meath dates to the Mesolithic period, approximately 7500 BC, when

communities of hunter-gatherers exploited the coastal, lacustrine and riverside environments. The

main indicators of Mesolithic activity in Ireland take the form of flint scatters and shell middens.

A general distribution map of known Mesolithic material shows a concentration of material in the

north Leinster area, second only to the dense clustering of material on the northeast coast of

Antrim and Down. Much of the island was impenetrable in this period due to the dense forest

cover which dominated the landscape; this included oak, alder, elm, pine and hazel. Mesolithic

communities made little impact on the natural environment. Where settlement occurred, it tended

to take the form of small seasonal camps such as those at Mount Sandel, County Derry and Lough

Boora, County Offaly (Waddell 2000, 23).

During the Neolithic period (c.4000–c.2400 BC), technological advances in the production of

stone axes and other tools allowed for the clearance of relatively large tracts of forest which

facilitated the development of the emerging farming culture which would arguably reach its zenith

in the Boyne Valley with the construction of the three passage tomb cemeteries (Newgrange,

Knowth and Dowth) at Brú na Bóinne. The cemetery as a whole comprises around forty known

passage graves ranging in date from c.3260–c.3080 BC. The cluster of around eighteen tombs at

Knowth contains the largest concentration of Neolithic art in Western Europe with some of its

finest examples.

The archaeological complex of the Hill of Tara covers the townlands of Castletown Tara,

Jordanstown, Castleboy, Fodeen and Belpere. The complex comprises at least seventy monuments

ranging from a Neolithic passage tomb to Iron Age ceremonial earthworks. The best known

monuments include Ráith na Ríg, Ráith Lóegaire, Tech Midchúarta (the Banqueting Hall), Ráith

na Senad (the Rath of the Synods), Clóenfherta (the Sloping Trenches), Ráith Gráinne, Ráith

Maeve (ME037:008), Tech Cormaic, the Forradh, the Lia Fáil standing stone and Dumha na

nGiall (the Mound of the Hostages) which is also a passage tomb. Many of these are mentioned in

ancient texts, poetry and oral lore. Outside the immediate environs of the hill itself are several

additional related monuments such as the linear earthwork in Castletown Tara and Riverstown

(ME031:040) and barrows such as that at Belpere (ME037:035).

Not all the monuments on the Hill of Tara are contemporary and there have been recent attempts

to describe the probable chronology and development of the hilltop monuments and their

relationship to one another. Newman has suggested eight broad phases for the monuments of the

hill (Newman 1997). Traces of a wooden palisade enclosure were discovered under the Mound of

the Hostages and may represent the earliest monument within the complex (c.3030–2190 BC).

The mound itself was constructed over a layer of burning which may represent the destruction of

the palisade. The Lia Fáil (the standing stone now located within the Forradh) may have been

located beside the passage entrance, similar to the location of the standing stone at the western

tomb at Knowth. The third phase of building at Tara is represented by the Banqueting Hall, a

linear earthwork which may have been a formal avenue or approach to the hill.

The Early Bronze Age saw the incorporation of a cemetery into the Mound of the Hostages and

the building of some of the barrows, which are dotted over the hilltop, probably including the

Forradh. These barrows continued into the fifth phase of building at Tara and the gold objects

found on the hill also belong to this phase. Ráith na Ríg was built in the Late Bronze Age in Phase

Six and some elements of Ráith na Senad also belong to this phase. This was further expanded

during the next building phase along with the construction of Ráith Lóegaire, Ringlestown Rath,

Rathmiles and Rath Lugh, outlying monuments which demonstrate a new relationship with

monuments outside the immediate confines of the hill itself. The eighth and final phase is

represented by the conversion of Ráith na Ríg into a defensive rather than ritual enclosure and the

construction of Tech Cormaic, the ringfort now attached to the Forradh.

By the third century AD, Tara had been adopted as the capital of Meath and, as the kingdom’s

power grew, it assumed the status of a High Kingdom, exercising authority over the entire island.

The first High King of Meath was Cormac Mac Art who is said to have reigned from AD 226 to

266. The first High King of Ireland was Niall of the Nine Hostages and, from AD 402 to 1169, his

descendants or those of his brothers are said to have reigned uninterrupted except for a short

period from 1002 when the title was usurped by Brian Ború (Coldrick 2000).

From the late twelfth century onwards, Tara formed part of the Anglo-Norman kingdom of

Meath. The land around Tara was held by the de Repenteni family while Skreen and the

surrounding area were controlled by their rivals, the de Feipo family. The church on Tara was

associated with the Hospitallers of Saint John of Kilmainham. The Hospitallers’ possessions,

including the church at Tara, were confirmed to them by Pope Innocent III in 1212. The church at

Tara continued to function as a parish church until the sixteenth century. The medieval church

was demolished in 1823 and replaced by the present building. Two standing stones are recorded

in the graveyard, one of which is carved with a sheela-na-gig. There are also some fine estates

and demesnes in the area; some of these have been adapted as golf courses or other leisure

facilities, but many still retain eighteenth and nineteenth century garden and demesne features.

The archaeological artefacts recorded by the National Museum of Ireland reflect the general

archaeological wealth of the area. A Neolithic mudstone axe (in private possession) is known

from Roestown; bronze axes from the Bronze Age periods are known from Jordanstown and

Skreen; and a number of inhumations and cremations from a number of sites throughout the area

are also recorded.

Archaeological Background

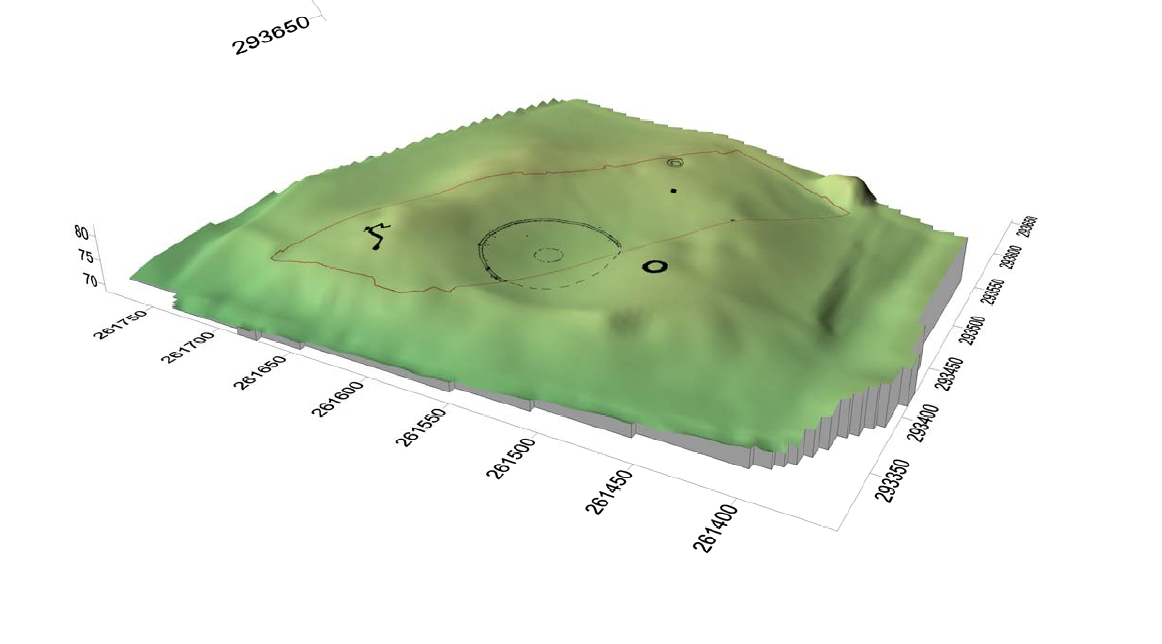

The concentration of known and identified archaeological sites indicates that the area within

Contract 2 has a very high potential for the presence of unknown archaeological sites and

features. The immediate area is dominated by the River Boyne and the Hill of Tara, which has

been the focus of extensive research projects in recent years by The Discovery Programme.

Placenames

River Lismullin is recorded in O’Donovan’s Ordnance Survey Names Book as the River Gowra or

Gabhra (O’Donovan 1836, 473). The parish and townland name, Lismullin, is given as Lois

muillean (the Fort of the Mill) by O’Donovan. This small river rises in Strandton and joins the

River Boyne at Dowdstown Bridge. The river reputedly fed Ireland’s first mill built on the

Lismullin River close to the testing area. The mill was reputedly built by the High King of Tara to

relieve his concubine of the arduous task of grinding by quern stone. A miller was brought over

from Scotland and the descendents of Lismullin Mill on the river traced their ancestors back to the

original miller according to O’Donovan (OS Letters 1836). However, it is unclear where the mill

was located in this townland. Several mills are shown on the early Ordnance Survey maps

(Figure 2). It is also worth noting the course of the river has substantially altered since the early

twentieth century along the eastern half of this survey (Figure 2, 3).

|

![]()