|

source - http://www.nuigalway.ie/archaeology/Tara_RoadsIreland_07.html

A rear-view perspective of Tara from the M3

for Roads Ireland magazine – (forthcoming December 2007)

Joe Fenwick, Department of Archaeology, NUI Galway.

Tara retains a unique cultural resonance for Ireland and for people of

Irish descent throughout the world. Though its archaeological legacy is

of enormous significance, it is the wealth of early historical,

mythological and legendary sources associated with Tara in addition to

its singular importance to Irish language, folklore and place-names

studies that truly sets this place apart. According to some of the

earliest literary sources, Tara was chief amongst the ancient

prehistoric royal centres of Ireland, serving as a major ritual

sanctuary before (and after) the coming of Christianity, a place of

royal inauguration and the seat of the high kings of Ireland. Indeed, a

number of these documents record that Tara, in recognition of the

central political and symbolic role that it continued to command well

into the historic period, was the central focus of five major roadways

(the Slige Asail, Slige Chualann, Slige Dála, Slige Mór and Sligh

Mudlúachra) which were said to have radiated to the furthest reaches of

the Island. Over the intervening centuries the political focus has

shifted and today all roads lead to Dublin; like the spokes of a great

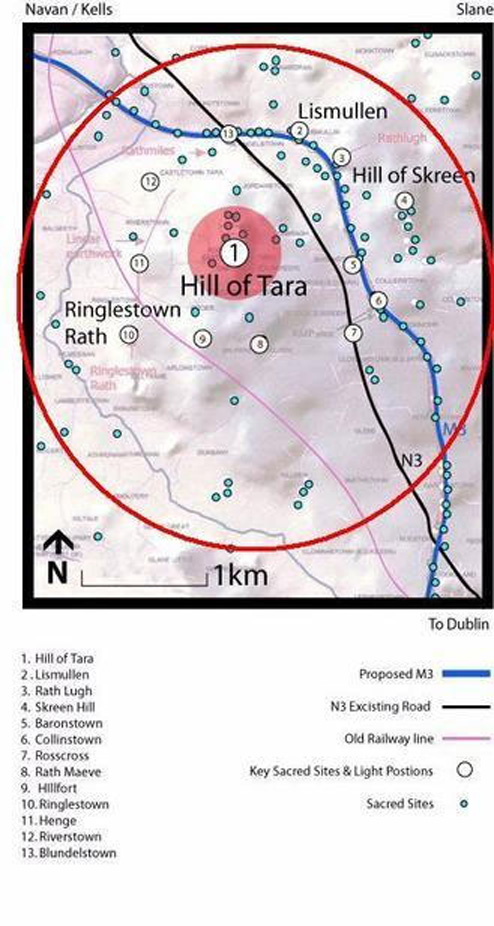

lopsided wheel converging on the M50. Of these spokes, three major

motorways (the M1, M2 and M3) will traverse Meath. The one currently

under construction, the M3, will bisect the royal demesne of Tara.

Tara has been the focus of State-funded archaeological and

historical research since the Discovery Programme was founded in 1992.

This work has yielded a wealth of new and exciting material, the

results of which are published in numerous peer-reviewed articles and

books (e.g. Conor Newman’s book Tara , An archaeological Survey

published in 1997 and Edel Bhreathnach’s edited volume entitled The

Kingship and Landscape of Tara published in 2006, to name but two). The

significance of Tara’s archaeological and historical landscape is

undisputed amongst scholarly and academic circles; indeed it was

recognised as such long before the current route for the M3 motorway

was chosen as the ’preferred route’ option. It has been demonstrated

conclusively, both archaeologically and historically, that the cluster

of unusual earthworks on the hilltop of Tara is but the nucleus of a

well-defined, integrated complex of archaeological monuments extending

into the surrounding landscape, a place universally acknowledged as one

of Europe’s foremost cultural landscapes. In an unbroken ritual

continuum over the millennia, the Hill of Tara has served as a

necropolis, ritual sanctuary and temple complex. This, in turn, served

as the backdrop to ceremonial pageantry and royal inauguration which

was to continue well into the Early Medieval period, long after its

religious authority had been supplanted by Christianity.

From humble origins as a passage tomb cemetery (dating to the

second half of the 4 th millennium BC) its importance grew with each

successive generation to reach its zenith during the Iron Age – at a

time when most of Britain and Europe was under Roman domination. In its

immediate hinterland are the physical remains of related prehistoric

barrows, cemeteries and ritual sites - such as the series of earthen

mounds in the Gabhra valley, the barrow cemetery of Skryne, the unusual

cemetery of mixed burial tradition at Collierstown (some 2000m to the

southeast of the Hill), the vast embanked enclosures of Rath Maeve and

Riverstown (situated 1600m and 1000m to the south and west of the

hilltop summit respectively), or the post-built ceremonial enclosure

with central temple at Lismullin (1600m to the northeast). The common

settlements and high-status royal residences of those who lived in its

shadow, who worshiped and ruled over Tara, were kept remote from the

hilltop sanctuary. It appears, therefore, that Tara is quite literally

a necropolis, a ’city of the dead’, and not a citadel as some had

speculated. The complexity of conjoined enclosures noted from aerial

photography at Belpere, for instance (situated approximately 800m to

the southeast of the hilltop), or the extensive multi-period earthwork

remains at Baronstown (lying midway between the Hills of Tara and

Skryne) are likely to represent the remains of high-status settlements.

At some stage in late prehistory the western and northern limits of

this broader surrounding hinterland were more clearly demarcated by a

series of defensive earthworks and fortifications. The remains of a

substantial double-banked linear earthwork, situated about 1000m to the

west of the Hill of Tara, can be traced for a distance of some 1600m.

Reinforcing this defensive earthwork is a semi-circular array of

equi-spaced fortifications (among them Ringlestown Rath, Rathmiles and

Rath Lugh) strategically placed to defend the western, northern and

northeastern flanks of the Hill and control passage through the Gabhra

valley. Together these monuments define a buffer-zone defending what

was, at this stage, a major political, religious and symbolic powerbase

from potential military incursion from the north. By the Early Historic

period (from around the 6 th century AD) the limits of this zone had

become more formally defined as the ferenn rí, or royal demesne, of the

kings of Tara. As if proof were needed of the significance of the

Gabhra valley and the connection between the Hill of Tara and its

sister hill of Skryne, a charter dating to AD 1285 mentions the

existence of a ’royal roadway that goes from the manor of Skryne to

Tara’ ( regalem viam qua itur de villa de Scryn versus Taueragh).

Tara retained its pre-eminent political role as ’caput Scotorum’

(capital of the Irish) and centre of kingship in Ireland throughout the

first millennium AD and beyond. For this reason it continued to serve

as the backdrop to major political and military upheavals up until the

present day. In AD 980, for instance, the battle of Tara witnessed a

decisive defeat for the Vikings of Dublin at the hands of the Southern

Uí Néill king, Máel Sechnaill II. As late as 1170 Roderick O’Conor was

inaugurated here as high king of Ireland. In more recent centuries,

Hugh (The Great) O’Neill was said to have rallied his troops on Tara

before marching to engage in battle at Kinsale in 1601. Again the

hilltop was chosen – as much for symbolic as strategic reasons – as the

location for a military engagement with crown forces during the 1798

rebellion. It was also the setting for one of Daniel O’Connell’s

monster meetings in August 1843, said to have been attended by a

million people. It is this fascinating convergence of tangible

archaeological remains illuminated by a very significant corpus of

historical documents and the extraordinary and pivotal national events

which unfolded here that sets this landscape apart. It is for this

reason also, that it is entirely inappropriate to build a four-lane

motorway and major floodlit interchange through it.

copied from - www.mythicalireland.com

|

![]()